Lance Todd Collection article by Mike Latham for RLCares

LANCE TODD by MIKE LATHAM

War hero, Home Guard officer, scratch golfer, broadcaster, journalist, thespian, professional sprinter, restaurateur, self publicist, master tailor, devoted family man- Lancelot Beaumont Todd achieved many things in his life away from the rugby field.

But it is his contributions to Rugby League for which he is mostly remembered, fondly to this day. As a player and later as a manager he was simply inspirational and had obvious star quality on and off the field. Todd, as he always reminded everyone, was the first overseas player, signing on for Wigan in 1908 four hours before his New Zealand team-mate George Smith signed on the dotted line for Oldham (after turning down Wigan’s overtures). After a break from the game Todd re-emerged as manager of Salford in the interwar period, revitalising the Club and presiding over their best ever period. He became involved as one the sport’s first broadcasters, had far-reaching ideas and visions for the game that went largely unheeded for decades. He was a superb judge of a player, knew how to put a team together and knew how to build success.

His death in a road accident was widely mourned but his name lives on in the Lance Todd Trophy, awarded to the Man of the Match in the Challenge Cup final. Visits to his gravestone in Wigan Cemetery have become a regular pilgrimage for Rugby League fans. Twice winner of the Lance Todd Trophy, Andy Gregory told me recently that, born and brought up close-by, he visits the grave on a regular basis, very much aware of Todd’s huge contribution to game’s history.

So where did it all begin? Lancelot Beaumont Todd was born in Otahuhu in Auckland City in 1883. As a young adult he was a small, dapper man, 5ft7 and ten stone, immaculately attired due perhaps to his training as a tailor. He played rugby from an early age and also developed a growing reputation as a ‘cash’ or professional sprinter. He once beat the then World Champion, American Arthur Duffy (Olympic champion in 1900) off a two-and-a-half yards start. On the rugby field he made up for his lack of height and weight with a remarkable eye for a gap which saw him cut through the strongest defences. His acceleration from a standing start gave him the edge over his opponents. Moreover, he could read the game, dictate play and had a great rugby brain, qualities that served him well.

Todd’s early career was spent with the Otahuhu Club where his two elder brothers played and in 1901 he joined the Suburbs club in Auckland on his father’s suggestion. He quickly made the first-team but then broke his collar bone on two occasions and was ruled out of action for nearly a year on doctor’s advice while he allowed the bones to set. In 1905 he joined (Auckland) City club on the suggestion of their captain and All Black George Tyler. He played at five-eighth, displacing the New Zealand international Peter Ward and when the Rugby Union All Blacks left for England achieved Auckland Provincial honours.

In 1906 Todd joined the Parnell club because the Suburbs club had become extinct. At the end of the season he toured Australia with the Auckland City team, but had to come back early after suffering from blood poisoning in his leg. He was in competition with many other talented players and struggled to earn further representative selection until he was invited for an All Black trial to play for North Island against South Island in 1907.

But Todd, unknown he thought to all but the promoters, had received an offer to join the professional 1907 All Blacks tour at the end of season. He refused, along with many other players, to sign an agreement not to go on the tour if selected. For his refusal to sign Todd was suspended by the Auckland Amateur body for three years without having a hearing. The suspension was later made into one for life, again without the option.

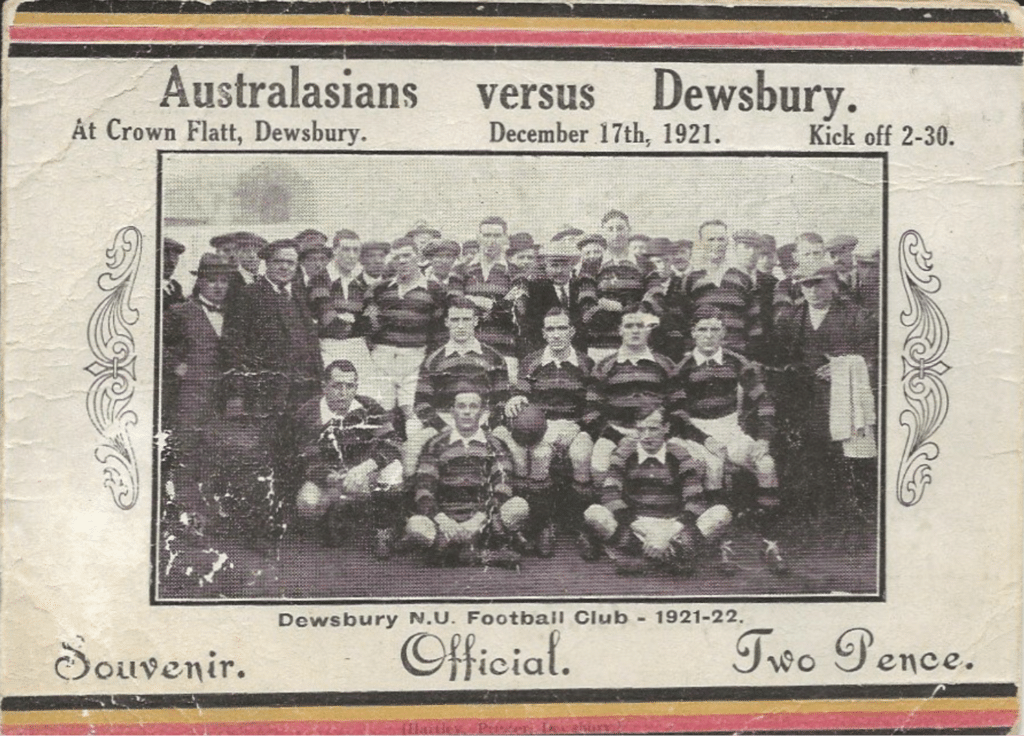

Todd did join the tour to England in 1907, becoming one of the pioneers who became known as the ‘All Golds.’ Prior to the tour, Todd was considered an upcoming player, but he impressed as the tour wore on, appearing in all three test matches and becoming one of the mainstays of the side. His performances in the last month of the tour, in particular, were outstanding as the New Zealanders recovered from losing the first test at Headingley to win the next two tests at Chelsea and Cheltenham and lift the series.

Todd learnt much from the experience which shaped his whole approach to the game. In an interview with the Wigan Examiner in April 1908 he said: “Undoubtedly the feature of your game is the wonderfully fit condition of the Northern Union players. It was the one great surprise to our boys. The returned amateur All Blacks had spoken very poorly of the Northern Union play and players generally and we naturally thought we had more than an outside chance. I frankly confess that we were fairly staggered. Probably the old ‘All Blacks’ never saw a game and had swallowed all they were told.

“As to the game itself, I still think it is a great improvement on the old style and cannot imagine anything better from a spectator’s point of view. For the players it certainly demands more preparation and I think getting into condition is one of the essentials for success.”

Todd also revealed in the interview that he had helped (tour promoter) Mr Albert Baskerville with his arrangements for the tour, an early sign that he was far more than simply a rugby player. He recruited several members of the side and told the story of one, un-named player who pulled out of the tour party just before it was announced after receiving £70 to stay behind and continue his connection with the Amateur Union.

It was very unusual for players to be directly quoted in newspaper articles or reports at this time and Todd’s interview was a departure from the accepted norm. From the outset he was a strong personality with firm views and opinions, far from the subservient player that many professional football clubs expected.

Todd’s displays captured the interest of Northern Union clubs and the ambitious Wigan club was an enthusiastic suitor. Wigan had enjoyed a revival in their fortunes after moving to Central Park in 1902 and attracted large crowds that made their finances more secure. Todd signed on for Wigan in the dressing room after the final test at Cheltenham on 15 February 1908, even though there was still one match of the tour remaining.

Prior to the tour the Northern Union clubs had made an agreement that the New Zealanders should not be approached until the conclusion of the official tour and there was some disquiet from outside that Wigan and Oldham had jumped the gun. Under the heading ‘Colonial for Wigan, Todd signs on’ the Wigan Examiner reported that “Secretary Mr George Taylor and Director Mr James Henderson, representing the Central Park organisation witnessed the third test match at Cheltenham on Saturday and subsequently made terms with Todd, the necessary papers being signed the same evening. “ They had also tried to sign Todd’s friend and former club-mate George Smith but he resisted Wigan’s overtures and instead signed for Oldham. Todd made a try-scoring Wigan debut four days later.

Smith, then aged 35 had signed for Oldham for a reported £150 but Todd’s signature was reported to have cost £400, an amount which according to one Manchester writer was “in accordance with Wigan’s liberal traditions.” Nevertheless, he added, “the Wigan officials express themselves well satisfied with their enterprise. Todd usually played at five-eighths but in the last two games was placed at wing three-quarter and at both Chelsea and Cheltenham he showed resource and pace.”

Wigan agreed to support Todd in obtaining his tailoring diploma and he spent some time in London at Savile Row. He soon became part of Wigan’s legendary three-quarter line of the Edwardian period, Leytham, Jenkins, Todd and Miller. Though the quartet was always referred to in that order Joe Miller was in fact the right-winger with Todd as his centre and Bert Jenkins and Jimmy Leytham played on the left. Lancaster born Leytham was a gentlemanly winger and prolific try-scorer who met a tragic end in a boating accident on the River Lune in 1916. Jenkins was a rock-solid Welsh centre who provided the perfect foil for Leytham. Todd’s partner was the only local from the quartet, Pemberton born Miller who lost little in comparison with Leytham in terms of try-scoring but was a very under-rated player.

Much later, in 1941, the Wigan Examiner veteran reporter Joe Leech reminisced about the qualities of each player- who between them scored 717 tries in 1,060 games for Wigan. “Leytham always acknowledged his debt to Jenkins, his brilliant partner,” Leech wrote. “Leytham was a prolific scorer and was probably the most popular player of his time in Rugby League. Jenkins was a man of exceptionally powerful physique and became a terror to opposing teams. Miller was the only Wiganer in the team. A stockily-built player, he had a fine turn of speed and he developed a clever swerve which enabled him to elude opponents who had cut across the field.

“Lancelot Beaumont Todd was the idol of the crowd at Central Park and was induced to join Wigan at the conclusion of Baskerville’s New Zealand team in season 1907-08. One of the lightest three-quarters who ever represented Wigan he compensated for his lack of weight by superior skill and resource and was always a marked man. ‘Toddy’, as he was known, knew all the tricks of the game. As a lightweight, he was easily thrown, when the opposing team could get at him, but he bounced like rubber and was soon up again and waiting for more. He could bluff cleverly and he was an ideal partner for Miller. His passes were well timed and, unless he was prevented from following-up, he was usually ready for a re-pass.”

The Northern Union game had only recently switched from 15 to 13-a-side and Wigan pioneered an exciting new approach to the game. Todd’s signing was the forerunner of several new signings as Wigan’s directors scoured the globe for talented players. Fellow New Zealanders Charlie Seeling, Massa Johnston, William Curran, Arthur Francis and Percy Williams were amongst those who followed Todd to Central Park alongside a host of players from South Wales.

By the time Todd played his final first-team match for the club in November 1913 he had become a major celebrity in the town. The bald facts are that he played in 185 matches, scoring 126 tries and kicking seven goals. He shared in Wigan’s inaugural Championship success in 1908-09 and was also a member of the first Wigan Challenge Cup Final line-up, losing to Broughton Rangers in 1911. During November 1910 he played twice for Lancashire alongside several other New Zealand born players and the Australian Mick Bolewski, who played for Leigh.

It quickly became apparent that Todd was far from just a rugby player. He was a keen thespian and joined Wigan Little Theatre. When Wigan won the Lancashire Cup in 1908 a celebration dinner was arranged for the evening but Todd was unable to attend as he had prior engagement as lead part in a theatrical production. He also opened a restaurant in Wigan town centre and in May 1911 married the daughter, Ann Blaylock Samuels, of a prominent Wigan gentleman, Charley Samuels. The wedding was held at Wigan Parish Church. Like Todd, Samuels had been a former ‘cash’ sprinter and he had been a prominent member of the Wigan rugby side in the rugby union days, a big friend of the influential Jim Slevin, the borough electrical engineer and the first Wigan superstar footballer.

Todd also had a shrewd eye for his own worth and his pulling power to a club attracting some huge attendances to Central Park. It was the custom for players in those days to receive a signing-on fee when they joined the club and effectively they would then be tied to the club for the rest of their career or until the club’s directors (who also selected the side) saw fit to transfer them. Not so with Todd who only ever signed-on for one season at a time, negotiating a new signing-on fee each time.

In May 1909 Todd’s adoring Wigan public awoke to the news in the Wigan Examiner– Todd’s regular mouthpiece- that he was to return home for good in the next month or so. Todd had been upset towards the end of the season that he had been dropped from some games in favour of the Welshman Gomer Gunn, a player he considered far inferior to himself. He hired a public hall to explain his decision and two thousand Wigan supporters turned up to hear him speak.

Todd stayed around until just before the start of the next season before setting off home, arriving in New Zealand in September 1909. He then conducted negotiations with the Wigan officials by cablegram. His brinksmanship worked as he was made an offer to return and came back in November 1909, re-signing for a reported £250 fee. When Todd arrived at Plymouth on the steamship ‘Arawa’ a deputation of four Wigan officials was waiting at the dock-side to greet him. They then proceeded to London by train where they enjoyed a production at Drury Lane Theatre, before continuing their journey back to Wigan the following day. When Todd arrived back in Wigan a massive crowd gathered on Wallgate to greet him as he emerged from the railway station and he spoke to the assembled throng.

Todd was never shy of publicity throughout his time at Wigan and was often the mouthpiece for the players, complaining to the officials on one occasion after the players only received some sandwiches after a long rail trip to a game at Hunslet. After Wigan’s victory in the Lancashire Cup Final in December 1912 he took the opportunity to speak to supporters at the celebration dinner held that evening at the Minorca Hotel in the town.

Todd again mentioned the fact that he was the oldest Colonial in the game, having signed on four hours before Smith and he never regretted coming to Wigan. “It is likely I will be leaving you in the course of a few months,” he added, “but I trust that Charlie Seeling and Percy Williams will maintain the reputation of the club. My heart will always be with you and I will be eager to learn in Auckland how you are faring. As to the Wigan team, each member is one of the thirteen and that is why we won our games.” Following an altercation with a committee member (Todd claimed he was insulted by the member) Todd said in December 1913 he would not play for Wigan again. The dispute was apparently resolved but Todd only played in the reserve team and was transfer-listed at £400 in January 1914.

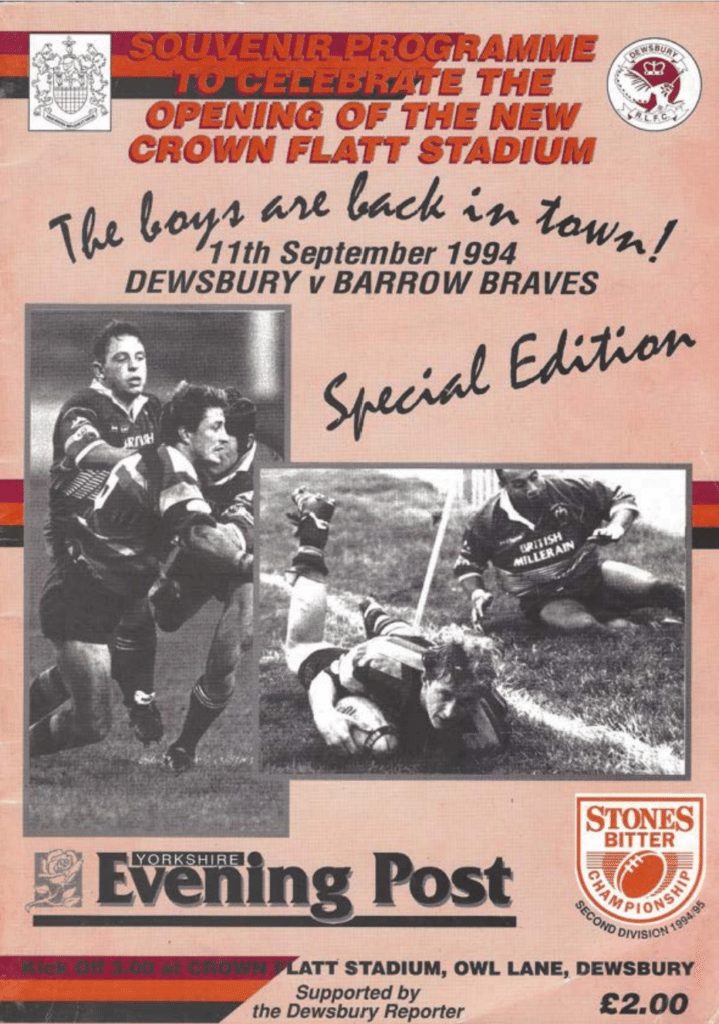

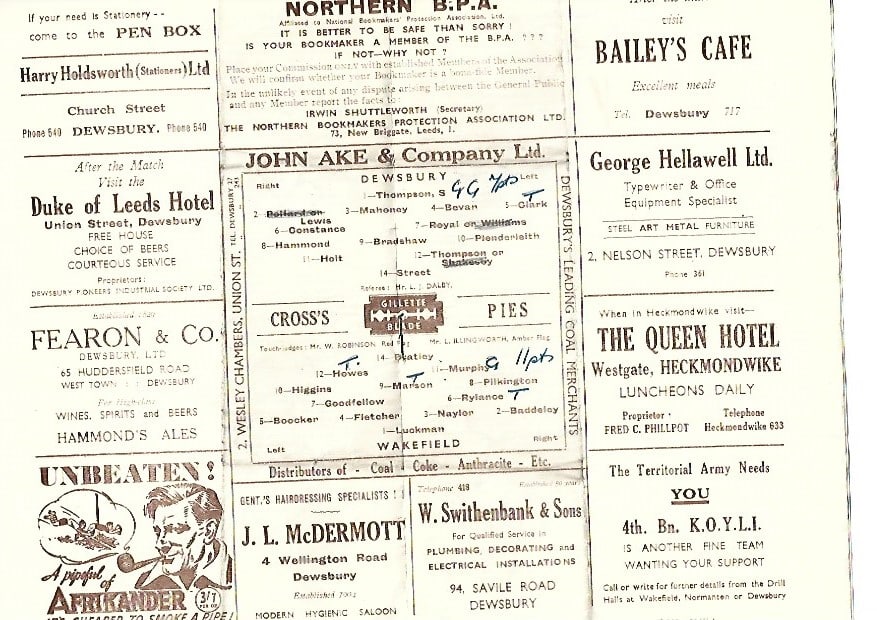

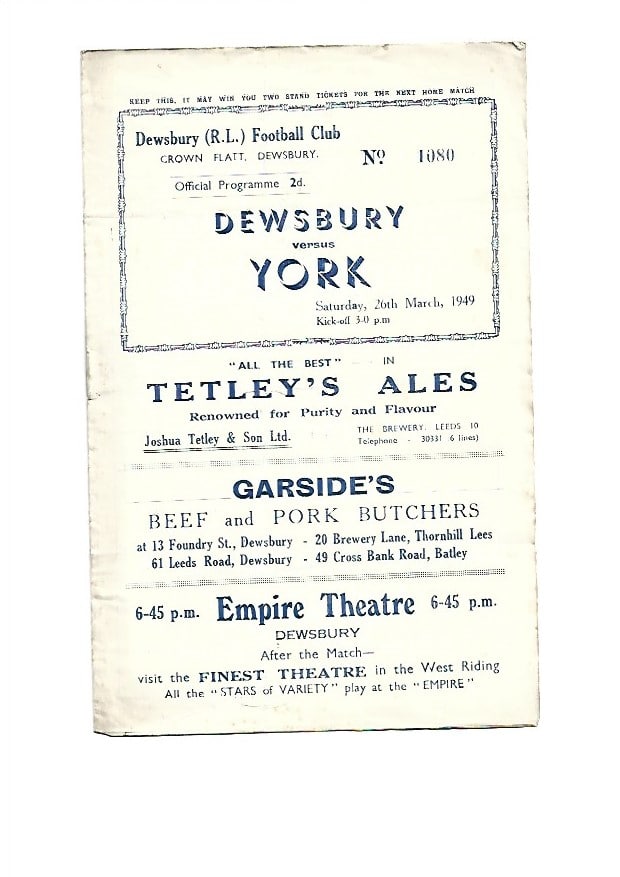

Todd was transferred to Dewsbury, making his debut against Hull KR on 17 January 1914. Todd’s popularity remained high with the Wigan supporters and some club members called a general meeting to express their dissatisfaction over his transfer and the manner of his departure from Wigan. The meeting, held at the Co-Operative Hall was described as ‘disorderly’ and at one stage the Wigan committee walked off the platform en masse after being roundly barracked. Todd was present at the meeting but was refused permission to speak as club officials stated he was no longer a member and not entitled to speak. When the meeting broke up in disarray Todd then took his opportunity to take to the floor to loud cries of “Well played, Dewsbury!”

Todd explained that he considered he had a right to be there so that if there were any miss-statements on either side they could be contradicted. The committee had treated him with contempt and if they were not men enough to remain on the platform he had nothing to say for or against them. There were doubtless faults on either side. Perhaps he had been bad to manage and they were bad managers but when a player had a grievance and took it to the committee he had a right to be heard. He was sorry to be leaving the Club but had not left the town. There was no doubting where lay the affections of the Wigan supporters.

Todd played eleven times, scoring three tries before the end of the season, but his time at Dewsbury was not a particularly happy one. When Wigan visited Crown Flatt the travelling supporters were dismayed to learn that Todd was not in the home line-up. It emerged that a deputation of Dewsbury players had met the directors prior to the game and presented a petition that stated Todd should be dropped from the side “as his performances did not merit his inclusion.” The directors agreed and Todd was left out. When news of this decision became known, many of the home supporters barracked their own players and directors throughout the match in scenes described as “increasingly ugly.”

With war clouds threatening football matters soon went on the back burner as the grim realities of the rapidly worsening international situation dominated attention. Little was then heard of Todd until a report appeared in the Sporting Chronicle (24 August 1916). This stated that obituaries for Rugby Union players was common in the leading ‘class’ papers (like The Times) but Northern Union players were not mentioned. It went on: “The Northern Union man is not in the way of gaining a commission like his Rugby Union counterparts. His education and vocation have not fitted him to pass the tests necessary to be an officer. Exceptions are Lieutenant Gwyn Thomas and Lieutenant LB Todd, but generally speaking the numbers are few.”

“Second-Lieut Lancelot B Todd, the famous New Zealand footballer, has been promoted lieutenant,” reported the Wigan Examiner in April 1916. “He joined a contingent of New Zealanders and saw service in Gallipoli, where he was given his commission.” Todd later rose to the rank of captain.

After the war was over Todd began a new life as a Secretary at the Blackpool North Shore Golf Club. There were 487 applications for the position which carried a salary of £250 per annum. He took over his new post in September 1921 and stayed on the Fylde Coast for several years. Occasionally reports appeared in local newspapers stating he had been successful in winning golf competitions. Todd planned returning to New Zealand in the late 1920s, but delayed due to his wife being unwell. In July 1928 he read an advertisement from Salford RL Club for the post of secretary-manager and successfully applied for the job.

Todd took up his duties at Salford on 1 August 1928, and was an instant success, taking the club from 26th in the league, prior to his arrival, to fourth position in his first season. In November 1933 he signed a new, seven-year contract agreement and he stayed with Salford until after the outbreak of the Second World War.

During his time with Salford Todd oversaw a remarkable run of success as his charges won the Lancashire Cup for the first time in the club’s history, defeating Swinton in the 1931 final and going on to repeat the success on three more occasions. Salford won the Championship three times, in 1933, 1937 and 1939 and were runners-up once (to Todd’s old club Wigan in 1934).

On the latter occasion, following Wigan’s 15-3 victory Todd entered the Wigan motor-coach just as it was about to leave the Warrington ground and addressed the Wigan players. “Congratulations to the Wigan team from an old Wigan player,” he said. “You have been the better team today. If we are in the final again next year I hope we shall beat you. If we are not in the first four I hope you will win the Cup again.”

Salford lifted the Challenge Cup at Wembley in 1938, defeating Barrow. They returned to the capital the following year but their side was stricken with a ‘flu virus before the game and lost to Halifax. They did recover remarkably, however, to defeat Castleford in the Championship at Maine Road the following week before a crowd of over 69,000 just as war clouds were looming again.

In 1934 the fledgling French Rugby League invited Salford to undertake a promotional six-match tour in an attempt to publicise the game. The tour was a huge success and Salford’s team proved to be perfect ambassadors for the game. They were dubbed ‘Les Diables Rouges’ or the ‘Red Devils’ by the French journalists, a nickname that has survived through the years.

Assessing Todd’s contribution to the Salford success, the hugely respected Club Historian Graham Morris told me: “When Todd arrived at Salford some of the future stars were already there- players like Barney Hudson and Billy Williams for example- but he extracted the very best out of the talented players at his disposal and moulded them into a fine side. His lengthy absence from the game had not impaired his judgement.

“Todd built a side based on flair and imagination and transformed the mood around the club virtually overnight from gloom to glory. In his first season he only added two players to the squad but their change in fortunes was remarkable. He was particularly good at spotting which rugby union players, especially Welsh players, would be able to make the transition to rugby league. He set up a network of scouts throughout the country and got regular tips and reports sent through to him. But he always insisted on watching the player himself, often more than on one occasion, before he signed them.

“Todd signed some remarkably talented players from Welsh rugby union, players like Gus Risman, Emlyn Jenkins, Billy Watkins, Alan Edwards and Bert Day but also had an eye elsewhere- the fullback Harold Osbaldestin from the Wigan area for example and the Cumbrian Sammy Miller.

“I don’t think Todd actually coached the side,” Morris continued. “The composition of teams was very different in those days. Todd signed the players, organised them, made all the arrangements for training and matches but he had a trainer to get them and keep them fit. Tactics, such as they were, were largely determined by a few of the senior players before a game. But Todd left no one in any doubt that he was in charge. He was the motivator before matches and Emlyn Jenkins once told me that Todd could change a game at half-time with one of his speeches in the dressing room.

“He presided over The Willows from his office in the old pavilion and always seemed to be at the ground at all hours of day and night. He was a very smart man, usually seen wearing a suit with waistcoat and watch chain and his hair immaculately groomed. Players that I spoke to of that era said that he immediately commanded respect but that he was also a very fair and kindly man. He looked after the players, made sure that off the field they had decent places to live, that their families were settled in the area. If one was ill or injured Todd would make sure they got the best medical attention. He was regarded as a father figure by his players.”

A Testimonial match was given in Lance Todd’s honour to acknowledge his ten years service to the club. The idea came from the Salford Supporters’ Association. In the programme notes, Todd singled out the club’s win at Wembley in 1938 as his greatest moment. “It was the culmination of years of hard work and the realisation of the dream of everybody connected with the club,” he wrote.

Todd’s contract with Salford was not renewed when it expired on 9 November 1940, due to the uncertain situation regarding the war. “It was ironic that the First World War effectively ended his playing career and the Second World War ended his managerial career,” Morris said. “Quite what he would have achieved but for the war is anyone’s guess, but he had the knowledge and the intuition to re-shape the Salford side and bring in new players as and when required.”

During his time at Salford Todd branched out, writing regular newspaper articles on the sport and then becoming a pioneering radio broadcaster on the sport. His articles were widely read and discussed and he was never afraid to ruffle a few feathers. “In many ways Todd was a man ahead of his time,” Morris points out. “Even in the early 1930s, for example, Todd was advocating summer Rugby League.”

An article from the Wigan Examiner of 11 July 1931 demonstrates Todd’s far-sighted approach. Entitled: ‘Summer Rugby – LB Todd’s Revolutionary Proposals – Wigan unfavourable’ the article showed Todd’s far-thinking, but also the opposition he met with his attempts to change the game.

“Lance Todd has dropped a bombshell into sporting circles by suggesting that the Rugby League should abandon winter football and play the game in summer,” the article began. “Briefly, Mr Todd’s revolutionary proposals are: Season to start on a Saturday nearest to March 1st and extend to early November; close season to part of November and the whole of December, January and February. In March, April, October and November time to kick-off 3-30pm. In May, June, July, August and September kick-off about 7-30pm.

“The advantages claimed by Mr Todd are: avoiding postponed matches for bad weather – there were nearly one hundred last season; affording entertainment for thousands at a loose end on summer evenings; supporters would accompany their teams in large numbers; evening training for players; economy in protecting grounds from severe weather; four months absolutely clear of Soccer opposition.”

One of the leading writers of the day, ‘Forward’ in the Athletic News canvassed opinions about Todd’s proposals. “Some are inclined to ridicule the suggestions, but I found a surprising level of support,” he wrote. “One level-headed club official said the period from November to February was a veritable nightmare for clubs and he would support the change to relieve himself of this burden.

“But should the miracle happen and the principle of summer football be approved, what then? Is the Rugby League prepared to stand alone as the one sport indifferent to the established and legitimate claims of every other? I am told that the Rugby League, in effect, stands alone. Mr John Wilson (Secretary of the RFL) says he will be sorry to see Rugby League football encroaching on summer games. And so will every real sportsman.”

The Wigan Examiner’s rugby writer, ‘Referee’ was more scathing. “A good many people in Wigan are not inclined to take the proposal seriously,” he wrote. “Coming from such a publicist as ‘LB’ one is not surprised at this view. Personally, I have never heard of such a revolutionary proposal connected with any sport and I doubt whether the proposal will ever take practical shape.

“Rugby is essentially a winter pastime and there is not the least likelihood of Rugby Union clubs following the League’s example if they were foolish enough to adopt summer Rugby.

“The brilliant work Mr Todd has accomplished for the Salford Club is its own answer to the scheme. If the clubs adopt a go-ahead policy and provide the right type of football, then Rugby League will prosper in winter. I have spoken to several members of the Wigan Directorate who regard the idea as impracticable, and have not the least doubt that this will be the general view.

“There are sports for summer quite enough to satisfy without the encroachment of professional Rugby. Let us think of those who play, watch and enjoy those games and be a little less selfish!”

Over 60 years after Todd’s ideas were first put forward Rugby League made the switch to being a summer sport.

In May 1937 Salford travelled to Leeds to play in an experimental 12-a-side exhibition game. The idea came from Lance Todd with each pack scrimmaging in a 2-3 formation. The entry of the ball into the scrum was improved and made play quicker but the radical step was never adopted.

When the Second World War started, Todd had joined the Salford Home Guard and he soon became second in command. He combined that role by maintaining his interest in rugby. In November 1940 the England-Wales wartime international at Oldham featured radio commentary by Todd. His knowledge of the game shone through his commentaries and he received many complimentary letters and comments from listeners.

In February 1942 the legendary Wigan fullback Jim Sullivan was the subject of a BBC Radio Broadcast in the ‘Giants of Sport’ series, compared by Victor Smythe (a well-known Manchester-based broadcaster and presenter of the period). Sullivan was interviewed by Todd who told him: “I’ll pay you this compliment. I’ve seen you as the Rock of Gibraltar- if ever a man has an example to set to young players that man is you.”

Tragically, Todd was killed in a road accident on (Saturday) 14 November 1942, when the car he was in hit an electric tram standard. Todd, then 59 was with his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel PR Sewell, who also died in the accident on Manchester Road, Oldham. It has been said they were returning from a match. His daughter was interviewed in May 2004 and she said they had tried to avoid a boy who lost control of his bike and was wobbling in the road.

The Lance Todd Man of the Match Award for the Challenge Cup Final was instituted by the Australian journalist and former tour and Wigan team manager Harry Sunderland, a friend of Todd’s, Warrington director Bob Anderton, who had been tour manager 1932 and 1936 and Yorkshire Evening Post journalist John B Bapty, who wrote under the name of ‘Little John.’ First awarded in 1946, the award was to be decided by votes cast by members of the press (and from its formation in 1961, members of the Rugby League Writers Association) present at the game.

The Red Devils Association was founded in 1953 by Gus Risman, Barney Hudson, Emlyn Jenkins and Billy Williams, and open to players who had played for Todd. At their meeting on 12 May 1956, it was proposed by Jimmy Lindley that a donation of £25 be made to purchase a permanent trophy for presentation to the winner of the Lance Todd award at Wembley, plus a replica to be retained by the player. It was decided to invite the recipient to the Red Devils reunion each year to receive his trophy, an event that has been a focal point of the evening ever since. The first player honoured was Leeds scrum-half Jeff Stevenson in 1957.

Todd’s interment at Wigan Cemetery following a joint memorial service (for himself and Lieut-Col Sewell) in Salford that was attended by thousands of mourners was an emotional day. His coffin was draped in the Union Jack and the bearers were members of the Wigan Battalion of the Home Guard. Many of his former team-mates, including Kiwi Charlie Seeling were present. The Home Guard detachment fired three volleys over the grave and then buglers sounded the ‘Last Post’ and the Reveille. There will never be his like again.